2D Signed Distance Fields

Introduction

During Thanksgiving eve, while my daughters ran around the house playing with their cousin, I spent the day learning about SDFs (I owe you, Becca). Signed Distance Fields (SDFs) represent geometry by answering a simple question: How far is any point from a given shape? Unlike defining a circle by its center and radius, or a square by its corners, SDFs provide a unified mathematical function that works for any shape.

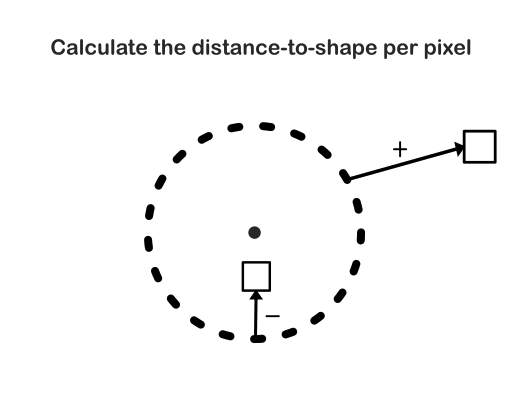

For each point in space, an SDF returns the shortest distance to the shape’s surface—positive if outside, negative if inside, zero on the boundary. This abstraction makes it trivial to combine shapes, create smooth blends, or render them efficiently.

Making a circle

Let’s start with a simple example: the SDF for a circle. Given a point $\mathbf{p}$, circle center $\mathbf{c}$, and radius $r$.

We compute the distance from the point to the circle’s center, then subtract the radius:

\[f(\mathbf{p}) = |\mathbf{p} - \mathbf{c}| - r\]Here’s the implementation in code:

fn sdCircle(p: vec2<f32>, c: vec2<f32>, r: f32) -> f32 {

return length(p - c) - r;

}

This gives us the signed distance for a given pixel: positive values mean the pixel is outside the circle, negative means inside, and zero means exactly on the boundary.

Rendering with SDFs

Once we have the signed distance for each pixel, we can use it to determine what to render. As you now know, the sign of the distance value tells us everything we need to know.

![]()

Pixels with negative distances are inside the shape. These are the pixels we want to color.

![]()

Pixels with positive distances are outside the shape, so we leave them uncolored. When the distance is exactly zero, the pixel lies precisely on the boundary of the shape.

That’s pretty much it, and that’s the beauty of it. A single mathematical function gives us both the distance and the inside/outside information we need for rendering. We can create different SDFs to render different shapes such as squares and triangles. We can even render 3D geometry, though we would achieve this through different methods, such as raymarching.

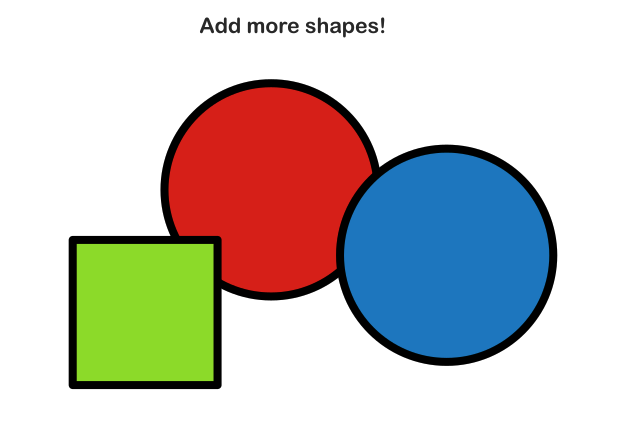

Combining Multiple Shapes

Now lets throw some more shapes into the mix. Instead of dealing with complex geometric intersections, you can simply combine the distance functions. From the pixel perspective, not much changes since we only care about whether we are inside or outside of the shape.

Each shape has its own SDF function. Here’s an example of another common primitive, a square:

fn sdBox(p: vec2<f32>, c: vec2<f32>, size: f32) -> f32 {

let d = abs(p - c) - vec2<f32>(size, size);

return length(max(d, vec2<f32>(0.0))) + min(max(d.x, d.y), 0.0);

}

How the Square SDF Works

The square SDF is more complex than the circle because we need to handle different regions: inside the box, outside the box (in different quadrants), and on the edges. Let’s break down each step:

Step 1: Transform to box-local space

abs(p - c)

First, we translate the point p relative to the box center c, then take the absolute value. This effectively moves the point into the first quadrant (top-right), which simplifies our calculations since a box is symmetric.

Step 2: Compute distance to box edges

let d = abs(p - c) - vec2<f32>(size, size);

Here, size represents the half-width (and half-height) of the box. By subtracting size from each component, we get a vector d where:

- If

d.xord.yis positive, the point is outside the box along that axis - If

d.xord.yis negative, the point is inside the box along that axis - If

d.xord.yis zero, the point is exactly on the edge along that axis

Step 3: Handle the outside case

length(max(d, vec2<f32>(0.0)))

When the point is outside the box, at least one component of d is positive. By clamping negative values to zero with max(d, vec2<f32>(0.0)), we get a vector pointing from the nearest corner of the box to the point. Taking the length of this vector gives us the Euclidean distance to the box.

Step 4: Handle the inside case

min(max(d.x, d.y), 0.0)

When the point is inside the box, both d.x and d.y are negative. The max(d.x, d.y) selects the component that’s closest to zero (least negative), which represents the distance to the nearest edge. The min(..., 0.0) ensures this value stays negative (or zero if on the edge).

Putting it together: The final return statement combines both cases:

- If outside:

length(max(d, vec2<f32>(0.0)))gives a positive distance, andmin(max(d.x, d.y), 0.0)is zero - If inside:

length(max(d, vec2<f32>(0.0)))is zero (since all components were clamped), andmin(max(d.x, d.y), 0.0)gives a negative distance

This elegant formulation handles all cases in a single expression, giving us the signed distance to the box boundary.

Smooth Blending

To combine shapes, you can use operations like:

- Union: Take the minimum of the two distances

- Intersection: Take the maximum of the two distances

- Subtraction: Combine with negation

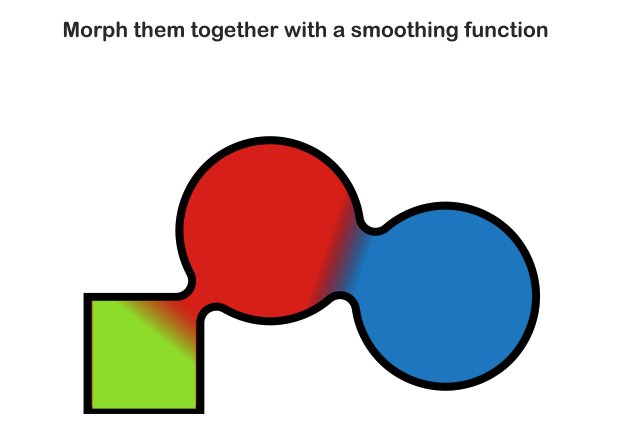

These operations work on the distance values themselves, making it trivial to create complex scenes from simple primitives. For now, we’re going to use a method to take the smoothed union.**

In my opinion, one of the most interesting features of SDFs is the ability to smoothly blend shapes together, creating organic, fluid forms that would be difficult to achieve with traditional polygon-based approaches. Now we’re sculpting with math (and a rendering pipeline, but we’ll leave that for a different post).

Instead of using a hard minimum or maximum to combine shapes, which would result in hard cutoffs when putting the shapes together, here we use smooth blending functions or smooth min to be exact. In general, these functions create gradual transitions between shapes, resulting in smooth, blob-like morphing effects.

The smooth minimum (or “smooth union”) function interpolates between the two distance values based on how close they are, creating a smooth transition zone. This is what allows SDFs to create fluid, organic shapes you see in modern graphics. The implementation below is by Inigo Quilez. Check out his blog for some pretty impressive use cases for smoothing functions:

// Author: Inigo Quilez

fn smoothMin(a: f32, b: f32, k: f32) -> f32 {

let h = clamp(0.5 + 0.5 * (b - a) / k, 0.0, 1.0);

return mix(b, a, h) - k * h * (1.0 - h);

}

The k parameter controls the smoothness of the blend—larger values create wider, more gradual transitions between shapes.

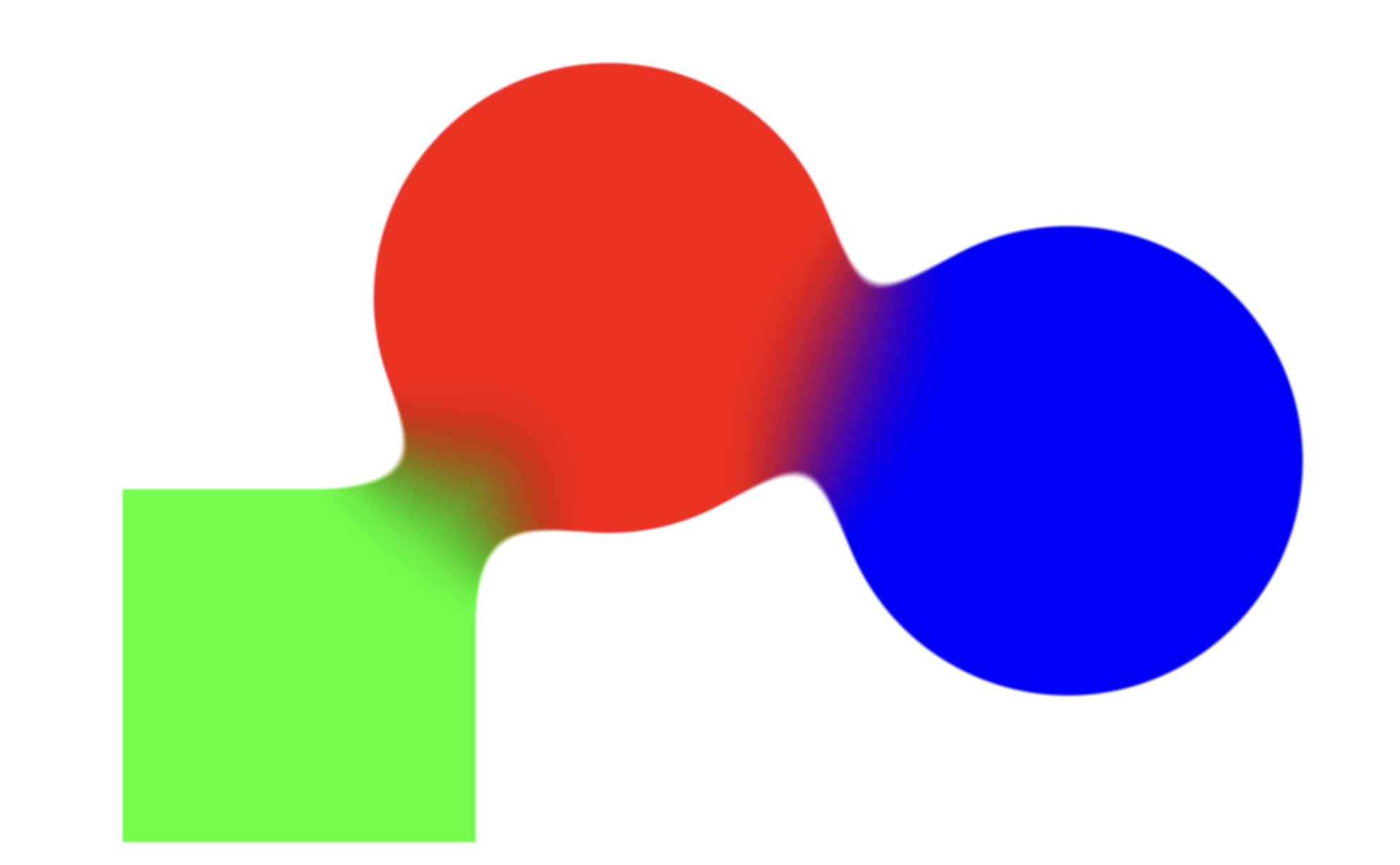

Result

When putting it all together (ignoring a bunch of WebGPU pipeline setup) I got the following result:

Full GitHub repo here.

As always, I hope you find this information useful or interesting. If you’d like to keep up on the latest, consider subscribing. Until next time!